Hucking Rules:

Rules are

treacherous terrain. In some people’s

minds, Kennedy’s, rules cripple a player and prevents him from ever being able

to play reflexively. While other’s,

Yngve, believe that Ultimate, like Jazz, cannot be improvised or taken solo

without a strong understanding of the structure and the fundamentals of the

game. Rules are further complicated by a

need to avoid “don’ts”. In fact the only

acceptable don’t, is don’t use don’t.

That aside, what ways

do we have to quantify a good huck? What

rules do we have in place that we can point to and say, “see good job!”?

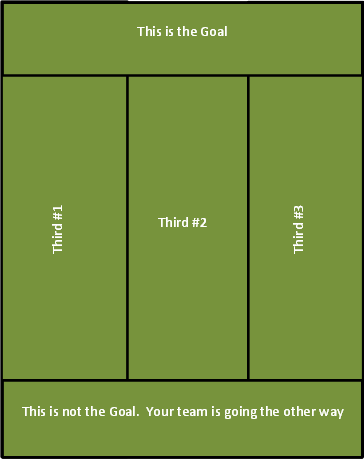

Thirds:

Same thirds is the

only hucking rule I’ve ever heard of.

The concept is simple: take the field and divide it vertically into

three thirds. If you, your receiver, and

the place you’re throwing too are all in the same third of the field then you

did a bad job. All other options are

good.

Simple enough,

however people seem to screw this up a lot.

Below is a field. On a completely

unrelated note, I often wonder why it is so difficult to grasp the orientation

of the field. I hope I’ve outlined it

completely below, if not imagine yourself inside the map.

Common misunderstandings:

1. The thrower and the place the disc was caught are in the same third, that’s bad.

a. False, there are three pieces not two.

2. The thrower and the receiver were in the same third, that’s bad.

a. False, there are three pieces not two.

3. The receiver and the place the disc was caught are in the same third, that’s bad.

a. False, there are three pieces not two.

Below is the same image as above with some dot’s on it:

T = Thrower

R = Receiver

C = Where the disc is caught

As you can see one of the two is not in the same third, therefore good huck. Any drawing where three dots are in more than one third is a good huck.

Below is the same drawing with new dots.

The three dots are all in the same third, bad huck. “But Bruns does the endzone count?” Yes. Yes it counts. Obviously the lines that split the field extend into the endzone, are you kidding me?

Triangles:

So far I’ve outline the rule of thirds. It’s easy, clear, extremely accurate, yet somehow incredibly difficult to grasp and apply quickly. The main issue people have with this rule is that they forget there are three pieces, not just two.

This is where my thought comes in. It’s the exact same as the rule of thirds, I just hope it’s easier to think about. I call it hucking triangles. The main advantage I see in the hucking triangle rule is that it is more dynamic, ignore the field and just look at the three pieces, what kind of triangle does it make?

Below is an image of a field. Again I hope it is clearly drawn.

Below is the same field with dots on it.

Again:

T = Thrower

R = Receiver

C = Where the disc is caught

Now, I’m about to do something crazy. Please brace yourself.

I have drawn a triangle. A good triangle is one that has large surface area, the more surface area on a triangle the better

This is a bad hucking triangle, due to how little surface area it covers. Terrible!

The Limits:

Just as with the rule of thirds, hucking triangles have limits. The most obvious is that silly cutters will believe that they should make their cut from R to C in the straight line that is drawn on the field. This is absolutely and comprehensively wrong. The cutter will not follow a straight line from dot to do, he will probably run down the field as he makes a read and curve into the disc. The point of the triangle is to connect where we are starting to where we end and summarizing, not to tell us how to get from here to there.

No comments:

Post a Comment